The illusion of stability in global supply chains has been permanently shattered by a convergence of geopolitical volatility and raw material scarcity.

For decades, manufacturing leaders prioritized lean principles that shaved fractions of a cent off unit costs while inadvertently creating brittle, single-point-of-failure networks.

The radiant truth that industry veterans discuss in private, yet seldom articulate in public shareholders’ meetings, is that Just-in-Time (JIT) delivery is mathematically incompatible with modern resilience requirements.

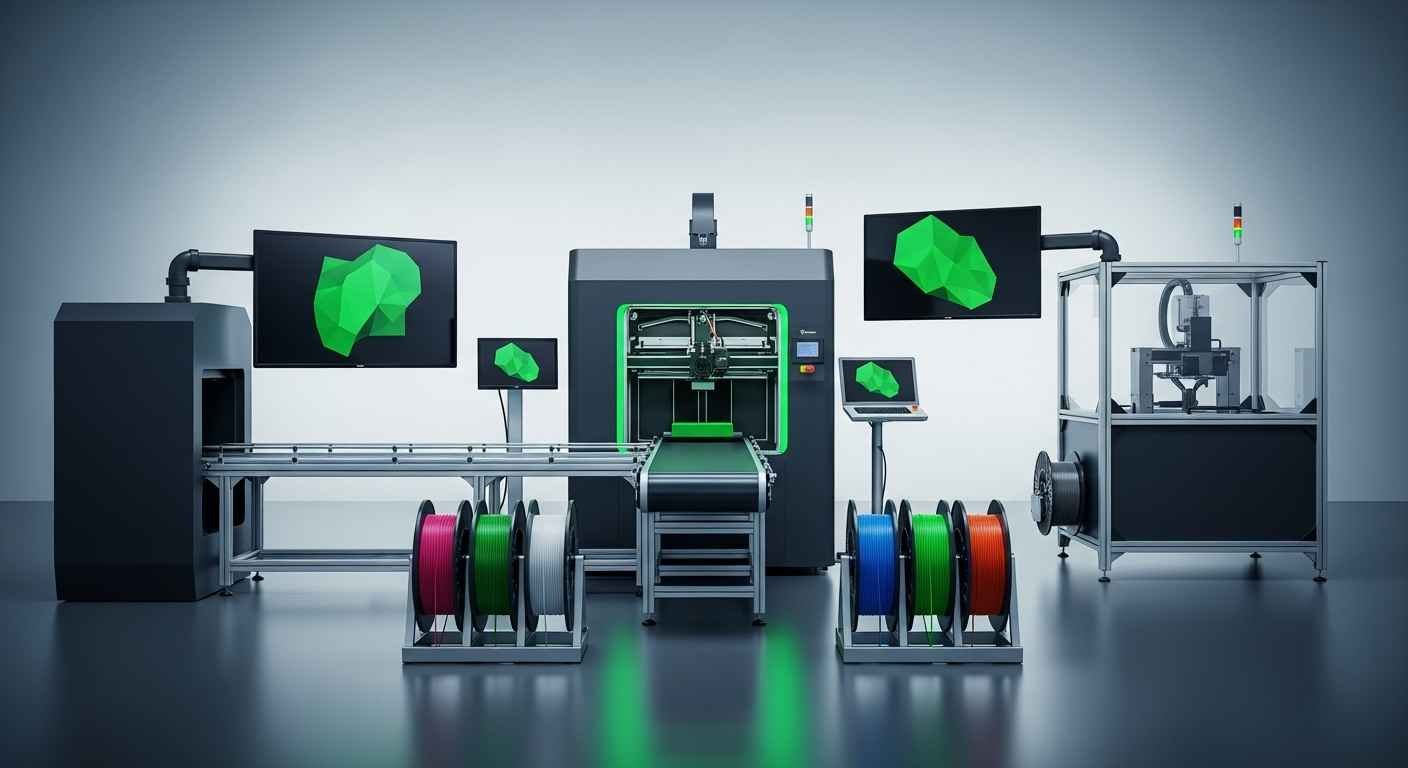

We are witnessing a fundamental inversion of the production paradigm, moving from centralized mass manufacturing to distributed, on-demand fabrication driven by advanced materials science.

This shift is not merely about adopting new hardware; it requires a complete architectural overhaul of how organizations conceive, validate, and distribute physical goods.

The future belongs to organizations that treat inventory not as physical stock in a warehouse, but as a digital library of validated files ready for localized materialization.

The Polymer Paradox: Moving Beyond Prototyping to End-Use Production

For too long, Additive Manufacturing (AM) was relegated to the model shop, viewed strictly as a rapid prototyping tool for aesthetic validation.

This “prototyping mindset” created a psychological barrier in the C-suite, masking the true capabilities of high-performance thermoplastics in operational environments.

The paradox lies in the material properties: early AM polymers like PLA lacked the thermal and mechanical stability required for factory floor applications.

However, the maturation of the polyaryletherketone (PAEK) family, specifically PEEK and PEKK, has fundamentally altered the engineering calculus.

These semi-crystalline thermoplastics offer chemical resistance and tensile strength comparable to aluminum, yet with a fraction of the weight.

Engineers must now decouple the concept of “plastic” from “cheap” and recognize these materials as advanced engineering composites capable of enduring high-stress cyclic loading.

Successfully transitioning to end-use production requires a rigorous understanding of glass transition temperatures and the anisotropy inherent in layer-by-layer construction.

The goal is not to replicate metal parts geometry-for-geometry, but to leverage the freedom of additive design to consolidate assemblies into single, printed units.

Supply Chain Decentralization: The Economic Case for On-Demand Manufacturing

The traditional manufacturing model relies on economies of scale, where the amortization of expensive tooling dictates minimum order quantities (MOQs) in the thousands.

This forces manufacturers to tie up significant capital in inventory that may sit dormant for months, accruing warehousing costs and risking obsolescence.

Decentralization through AM obliterates the tyranny of the MOQ by enabling the economic production of “batch size one.”

By positioning industrial printers at the point of need – whether a remote mining site or a regional distribution hub – companies can virtually eliminate last-mile logistics for critical spares.

This strategy shifts the cost center from logistics and warehousing to design engineering and material procurement.

The economic impact is measurable not just in reduced shipping costs, but in the restoration of operational uptime.

“The most expensive part in any manufacturing ecosystem is not the one with the highest material cost, but the missing fifty-cent gasket that halts a multi-million dollar production line. Additive manufacturing acts as an insurance policy against this operational paralysis, converting potential downtime into a manageable print-queue task.”

Partners capable of bridging the gap between digital design and physical execution, such as Aaryak Solutions, represent the new class of industrial facilitators essential for this transition.

We are moving toward a “send file, not parts” ecosystem where the intellectual property travels globally, but the physical product is born locally.

Horizon 1: Immediate Optimization of Spare Parts Management

The immediate application of this technology – Horizon 1 – focuses on the “long tail” of the supply chain: slow-moving, high-criticality spare parts.

Legacy equipment often relies on components that are no longer manufactured by the original OEM, forcing companies to cannibalize old machines or pay exorbitant premiums for custom tooling.

Reverse engineering these components for 3D printing provides an immediate return on investment by extending the lifecycle of capital assets.

The strategic roadmap begins with a comprehensive audit of the digital inventory to identify parts suitable for polymer or metal additive replacement.

Factors for selection include geometric complexity, material requirements, and the cost of downtime associated with part failure.

Success in Horizon 1 is not defined by printing everything, but by printing the right things that alleviate immediate supply chain friction.

This phase builds internal confidence and establishes the validation protocols necessary for more ambitious applications.

Horizon 2: Integrating Advanced Composites and Metal Replacement

Once the digital workflow for spares is established, organizations must advance to Horizon 2: active metal replacement using continuous fiber-reinforced composites.

Materials reinforced with carbon fiber, fiberglass, or Kevlar offer strength-to-weight ratios that exceed 6061 aluminum while allowing for complex geometries impossible to machine.

This capability allows for the fabrication of custom jigs, fixtures, and end-of-arm tooling that are lighter and more ergonomic for operators.

Reducing the weight of robotic end-effectors reduces the load on the arm, increasing speed and reducing wear on the automation equipment.

However, this horizon demands a higher tier of material science expertise, specifically regarding fiber orientation and load path optimization.

Engineers must learn to design for the process, utilizing software that simulates stress distribution to optimize fiber placement.

The result is a manufacturing floor that is agile, capable of retooling in hours rather than weeks.

Horizon 3: Generative Design and Distributed Digital Inventories

Horizon 3 represents the visionary state where human engineering collaborates with artificial intelligence through generative design.

In this phase, engineers input constraints – loads, materials, and mounting points – and algorithms generate optimal geometries that minimize mass and maximize performance.

These organic, lattice-filled structures are often unmanufacturable by traditional subtraction methods, making them the exclusive domain of additive manufacturing.

Simultaneously, the physical warehouse is largely replaced by a distributed digital inventory, secured via blockchain to ensure IP protection and traceability.

When a part is ordered, the license is authenticated, the file is streamed to a certified local printer, and the object is fabricated on demand.

This creates a supply chain that is immune to shipping blockages, tariffs, or regional conflicts.

It transforms the manufacturer from a producer of goods into a provider of certified manufacturing solutions.

Overcoming Material Fatigue and Layer Adhesion Challenges

Despite the strategic advantages, the physics of layer-wise construction introduces technical hurdles that must be managed with scientific rigor.

The primary concern in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and similar processes is Z-axis weakness, caused by incomplete polymer chain entanglement between layers.

While an injection-molded part is isotropic (uniform strength in all directions), a printed part is anisotropic, often significantly weaker in the vertical build direction.

To mitigate this, process parameters such as nozzle temperature, chamber heat, and print speed must be dialed in to maximize fusion.

Furthermore, post-processing techniques like annealing – heating the part to its crystallization temperature – can relieve internal stresses and improve bonding.

Failure to account for these material behaviors leads to catastrophic delamination under load.

Rigorous mechanical testing and finite element analysis (FEA) specifically calibrated for orthotropic materials are non-negotiable prerequisites for critical applications.

The Cost-Benefit Matrix of Post-Processing Workflows

A common oversight in the adoption of additive manufacturing is the underestimation of post-processing costs and time.

The print is rarely the finished product; support removal, surface smoothing, and dimensional sizing often constitute 40% of the total part cost.

Vapor smoothing, which uses chemical solvents to seal the surface and improve aesthetics, also significantly alters the mechanical performance and sterility of the part.

Decision-makers must analyze the “Total Cost of Validation,” which includes not just the printing, but the labor and equipment required to bring the part to spec.

Automation in post-processing – such as tumbling and depowdering systems – is essential for scaling from prototyping to production volumes.

Without efficient post-processing workflows, the speed advantage gained during printing is lost in the finishing room.

Strategic investment in finishing technology is as critical as the investment in the printers themselves.

Evaluating Internal Adoption: A Metric-Driven Approach

Technology implementation fails not because of hardware deficiencies, but due to cultural resistance within the engineering and procurement teams.

To gauge the health of an additive strategy, organizations must measure the sentiment and adoption rates of their internal stakeholders.

The following table provides a framework for interpreting Net Promoter Scores (NPS) specifically within the context of internal technological adoption.

Include a ‘Net Promoter Score (NPS)’ segment interpretation table.

| NPS Segment | Score Range | Internal Persona Profile | Strategic Implication for Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoters | 9 – 10 | The Agile Innovator: Design engineers who actively re-engineer legacy parts for AM. They value speed and geometric freedom over traditional constraints. | Empower these individuals as “AM Champions.” Give them budget autonomy for material testing and rapid iteration to demonstrate quick wins to the wider org. |

| Passives | 7 – 8 | The Skeptical Pragmatist: Operations managers who see the utility for jigs/fixtures but doubt end-use reliability. They require more data before full commitment. | Target this group with rigorous QA data and case studies. Demonstrate material certification and fatigue testing results to convert them into Promoters. |

| Detractors | 0 – 6 | The Legacy Guardian: Procurement officers focused solely on “unit cost” vs. “total landed cost.” They view AM as an expensive alternative to mass molding. | Do not argue on unit cost. Reframe the conversation around inventory carrying costs, downtime avoidance, and supply chain insurance. Show the cost of not having the part. |

Quality Assurance and Standardization in Additive Workflows

The final barrier to widespread industrial adoption is the establishment of a robust Quality Assurance (QA) framework that mirrors the reliability of ISO standards.

Unlike subtractive manufacturing, where material properties are defined by the billet, additive manufacturing creates the material and the part simultaneously.

This requires in-situ monitoring technologies that can detect process drift – such as thermal fluctuations or nozzle clogs – in real-time layer by layer.

Reference to intellectual property such as USPTO Patent 11,298,881 regarding automated additive manufacturing systems highlights the industry’s push toward closed-loop control systems.

These systems ensure that every voxel of the printed part meets the specified density and thermal history requirements.

Standardization bodies are currently racing to codify these parameters, but market leaders are establishing their own internal certification protocols.

“In the additive era, quality assurance is not a post-production inspection step; it is a continuous, data-driven dialogue between the hardware, the material, and the digital file during the genesis of the object. Without this digital thread of traceability, a printed part is merely a shape, not an engineered component.”

Documentation of these processes is critical for regulatory compliance in sectors like aerospace and medical devices.

Ultimately, the transition to additive manufacturing is a leadership challenge that requires balancing the immediate operational wins with a long-term vision of digital transformation.